Article

posted 7th May 2025

Universal Basic Income

Introduction

Imagine being able to cut down on the amount of time you spend in the workplace by 30% and still have enough to make ends meet. Imagine reducing your toil by that amount to still have money left over. Now imagine your government providing a monthly payment – no strings attached – that enabled that to happen. If this presents as being far-fetched or almost delusional, you should know that Universal Basic Income (UBI) is currently cited by a wide range of economists, social scientists, politicians and industrialists, not only as a means to lift millions out of poverty, but a mechanism whereby the whole of society could benefit.

While there are myriad definitions of UBI online, the Basic Income Earth Network define it as having five main characteristics:

1) Periodic – paid at regular intervals and not a one-off grant.

2) Cash payment – not a voucher system or paid in kind as food or services.

3) Individual – paid to everyone in a household and not the household total.

4) Universal – paid to all.

5) Unconditional – it's not means tested or subject to review (1).

The 'basic' aspect refers to it being an amount covering just that – the basics – and it's not designed as a means to dis-incentivise people from working altogether.

Now you would have to be forgiven in thinking that UBI is a novel idea. It's actually nothing but and has a long and storied history. In his superlative introduction to the subject, 'Basic Income: And How We Can Make It Happen', Guy Standing writes of UBI as having presented historically in a series of waves. The first encapsulates a time frame that harks back to ancient Athens.

First Wave

In 461 BC, Pericles and Ephialtes were the then ostensible leaders of the 'plebeians' in that great city. Ephialtes first initiated democratic reforms that meant Athen's citizens were paid for their jury service, but after his assassination by political opponents, it was left to Pericles to expand on this idea of a 'citizen's income' by instituting a basic income grant. This was to encourage the precariat population to engage with the polis (political life) of Athens, and was awarded whether an individual took up that duty or not.

As such, it was a system of deliberative democracy with a basic income acting as a means of facilitating civic involvement (2). Certainly if I was offered money to more meaningfully engage with politics I'd be all for it, but in keeping with what will be a regrettably recurrent trope, this initiative was sadly short-lived due to a coup in 411 BC. It wasn't until the 13th century AD that the idea of a basic income re-appeared, this time in medieval England.

In June 1215, the Magna Carta was issued as a document that put into writing such principles as the King and his Government being not above the law, while also granting rights and liberties to groups and individuals throughout society (3). Contained within were a set of new rules pertaining to 'the forest', and in 1225 after some adjustments to the original, the 'Charter of the Forest' was published in its definitive form (4).

It's a radical document and it's not an easy read. But from it's verbose and sprawling prose, some pertinent themes emerge from what's in effect the world's first environmental act. Indeed, some writers cite it as providing the intellectual founds on which UBI might be built (5), and it effectively re-introduced the idea of a basic income in the form of 'estovars', which were payments made to those widows who opted not to re-marry. This pleasing nod to feminist ideals entailed those women being provided food, fuel and building materials gleaned from a common pool, and it was the duty of the local parish to make sure such assets were made available (6). Such is the impact of this document, that Guy Standing in celebrating it's 800th anniversary, wrote that, 'everybody who calls themselves ‘green’ or ‘left’ should lift a glass of something special in salute to the principles it espouses' (7).

As to exactly how long the provision of estovars were made available is hard to tell from the literature, but Standing writes that the church was required to read the Charter to congregations four times a year throughout the 13th century, with every widow having the right to this basic income (8). Of course widow's pensions are now a staple of modern life, but even with this rich political history and enlightened outlook, it seems the idea of a basic income didn't really take root in the collective minds of our forebears until it was dished up as fiction by Thomas More in his seminal work, 'Utopia'.

Published in 1516, More's imagination ships us to his island state where poor citizens are provided a means of financial aid in order to thwart thievery amongst the criminal classes (9). As such, it's not a truly universal basic income, but it did plant a seed or two. Indubitably inspired by reading More's book, his friend Johannes Vives instantiated a trial in Bruges by impressing upon its Mayor the utility of such a scheme (10). Again, the emphasis was on targeting certain populations, and while not universal, the scheme has been credited in supplanting church charity with that of governmental aid.

Later in Enlightenment France, Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet, expounded on Vive's ideas, 'arguing that the distribution was to be done for the people’s entitlement instead of out of compassion' (11). This in effect moved the idea of such grants from the realm of welfare to that of state provided income. It was certainly a radical idea (Condorcet died in prison in 1794), but it was further celebrated by Thomas Paine in his 1797 essay 'Agrarian Justice'.

In what's a rebuttal to the religious thinking of the time – that poverty's divinely ordained - Paine took the wholly rational view that it's man-made, and that the State had every obligation to ensure an individual's economic rights were protected by the fair re-distribution of accumulated wealth created by private property (12). While Paine's ideas were championed by English and European writers, Standing cites 'communist fervour' (13) as effectively banishing such thinking once again to the fringes. It took World War I to bring it back to prominence.

Second Wave

World War I had a devastating impact on the working classes, with huge swathes of the post-war populace suffering under the auspice of the Great Depression. At this time, UBI found a venerable advocate in Bertrand Russell, the Nobel-prize winning philosopher, mathematician and social reformer (14). In the early 1930s at the height of the Great Depression, millions were out of work and idle at home. As such, Russell not only called for economic reform, but asked that we fundamentally re-assess our relationship with the workplace (15).

Russell espoused the view that humans are more than just workers, and in combining principles both rebellious and progressive, wrote in 'Roads to Freedom' in 1918: 'Anarchism has the advantage as regards liberty, Socialism as regards the inducement to work. Can we not find a method of combining these two advantages? It seems to me that we can. […] Stated in more familiar terms, the plan we are advocating amounts essentially to this: that a certain small income, sufficient for necessaries, should be secured to all, whether they work or not' (16). This is as pertinent and concise a summation of UBI as I've read online, and his idea of a 'vagabond's wage' (17) was discussed at length at the Labour Party conference in 1920, albeit when granted the more pleasing monicker of 'state bonus' by the Quaker and engineer Dennis Milner (18). It was unfortunately rejected the following year. It wouldn't be the last time such an idea foundered politically in the modern era.

Third Wave

Writing in Newsweek in 1968, Milton Friedman describes how 'more than 1,200 economists from 150 different colleges and universities signed a petition favouring a negative income tax' (19). Negative income tax was an idea propounded by Friedman in the early sixties as a means to improve the welfare system and to alleviate poverty. While not a UBI scheme per se, it's aim was somewhat similar. As opposed to providing welfare payments in the guise of food or clothing stamps, NIT put cash directly in the hands of those who needed it, and meant they could spend it however they pleased.

It's a more complicated scheme than that of a UBI, and the best explanation I've found online is that of Rebecca Linke, writing for the MIT Sloane School of Management:

'Theoretically, this would work by giving people a percentage of the difference between their income and an income cutoff, or the level at which they start paying income tax. For instance, if the income cutoff was set at $40,000, and the negative income tax percentage was 50 percent, someone who made $20,000 would receive $10,000 from the government. If they made $35,000, they would receive $2,500 from the government' (20).

It's designed to ensure that those who work will end up with more than those who don't, and of the five NIT experiments that were carried out by the United States between 1968 and 1980, over 300 scholarly articles were generated (21). So there's a veritable thicket of scholarship to hack through here. Fortunately, that's already been done by others.

Writing in 'Utopia for Realists', Rutger Bergman describes the findings of what were the first large-scale social experiments involving both control and experimental groups. In the States, this entailed 8,500 individuals from New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Iowa, North Carolina, Indiana, Seattle and Denver being granted this form of basic income. The research that amassed on the back of this wanted answers to three pertinent questions: Would people work less? Would it be too expensive? Would it be politically feasible? The answer to all three was found to be 'no' (22).

It's incredible to think that this scheme was nearly given the green light in the States. In 1970, under the aegis of President Richard M. Nixon and his Family Assistance Plan, the US Senate came exceptionally close to implementing a basic income policy, only to have it rejected by the US Senate (23). Ironically, it was pushback from the Democrats that nixed the deal. They reportedly claimed it didn't provide enough of a basic income. So the following year, Nixon presented a revised version of the policy, only for it to fail on the back of findings from the Seattle trial.

While there were plenty of noteworthy statistics generated from the NIT trials regarding improvements in health and better educational attainment (24), a purported outcome of the Seattle study was that it caused an increase in divorce rates by 50%. The conclusion drawn was that a guaranteed basic income empowered women too much, and this apparently overshadowed the other findings. That the numbers were revealed a decade later to be the result of a statistical error (25), only compounds the sense of an incredible opportunity being well and truly lost here. North of the border, a similar fate befell a Canadian trial, albeit for slightly different reasons.

Dauphin, Canada

It would be remiss of me not to mention the trial that took place in the Canadian town of Dauphin. It differed somewhat from the trials that took place in the US, in that those studies involved individual families spread out over wide areas of the states and cities they were conducted in. Consequently, the communal impact of such trials were hard to ascertain. By comparison, the Canadian trial focused its attention on 13,000 people living in one town, with $56 million dollars spent over the course of four years on 1,000 families - all of whom received a check each month with no restrictions - starting in February 1974 (26). A family of four received what would now be the equivalent of $19,000 per annum for the duration of the study, which was summarily dispensed with when a new conservative government took office.

Apparently the new administration held the idea in such low regard they refused to fund an analysis of the trial's results, and the 2000 odd boxes of notes, interviews and data were simply packed away unanalysed. It wasn't until Eveyln Forget (a professor at the University of Manitoba) tracked them down to the National Archives in 2009, that the experimental findings finally came to light (27). The results of 'Mincome' (minimum income) were that the trial had been a resounding success.

The veracity of Forget's findings were bolstered somewhat by the introduction of Canada's Medicare program in 1970. The Medicare archives meant that Forget had a wealth of data to compare Dauphin to neighbouring towns (which acted as ostensible control groups), and the comparisons were truly revealing. Of particular interest was the significant positive effects the experiment had on health. Hospitalisations were down a whopping 8.5%, and there were also dramatic decreases in domestic violence and mental health complaints. In addition, the birth rate dropped as young people postponed getting married, school performance improved significantly; and what had to be of real interest to skeptics, was the minimal effect it had on total hours worked by either men or women. Even effects further downstream of the trial could be observed, as Forget ascertained a positive influence on the income and health of the next generation. What's not to like here?

Taken together, the trials are sufficient to assuage the doubts of those nay-sayers who promulgate the view that basic income would only make people lazy. That just doesn't emerge from the data. In fact, when folk did cut down on time spent in the workplace, it was so they could look after their children or continue with schooling. It's the sort of labour market withdrawal you would welcome. That the health of a whole town could be improved with an injection of cash is wholly apparent in the findings from Canada, and to think that Mincome was seen as a pilot to be eventually rolled out nationwide, merely aggravates the sense I have of a political opportunity sorely missed that side of the Atlantic. Who knows what might have transpired if they'd been possessed of courage enough to act?

Fourth Wave

This brings us right up to the modern day. Guy Standing writes that this final wave 'started in a quiet way with the establishment of the Basic Income European (now Earth) Network (BIEN) in 1986' (28). Since then, there have been two seismic events - the crash of 2008 and COVID - that has meant interest in this subject has increased dramatically. The Stanford Basic Income Lab's webpage cites 192 trials as concluded or active, taking in basic income pilots that have been carried out in Canada, USA, Brazil, UK, Spain, Finland, Sierra Leone, Kenya, Namibia, Iran, India, Mongolia, China, Japan and Indonesia (29).

Now there are plenty of reasons why a UBI might be of interest in a post-crash or post-pandemic world. I think we've all felt the squeeze regarding costs of food, fuel, housing and hospitality, and as is the unfortunate norm, there've been no substantive increases in our wages to offset these costs. What with the world being in the state it is – we are currently experiencing a level of global conflict not seen since the Second World War (30) – it stands to reason that ameliorative measures like UBI might be applied by a government if need be. It's not as if we don't have the technical nous to do so. COVID payments and furlough schemes were rolled out in no time, so the necessary infrastructure and know-how are indubitably there.

In addition, there are also the threats of automation and AI to contend with, and there's plenty of literature describing what an AI realised world might look like (31,32,33). It must be said, none of them describe a particularly pleasing future for our current workforce. Huge numbers of meaningfully employed folk are under threat from automated driving (34), and many aspects of the creative industries are becoming increasingly undermined and de-valued as this technology incrementally ramps up its abilities (35). Of course these predictions are at present just that, and I'm cognisant of maybe distracting the reader from what a UBI is actually designed to do, which is in the main to eradicate poverty. But before I start wrapping this article up, I can't complete a whistle-stop tour of the subject without drawing attention to what I feel is the most salient of reasons for it's roll-out: You're supposed to be better off anyway.

Closing the jaws

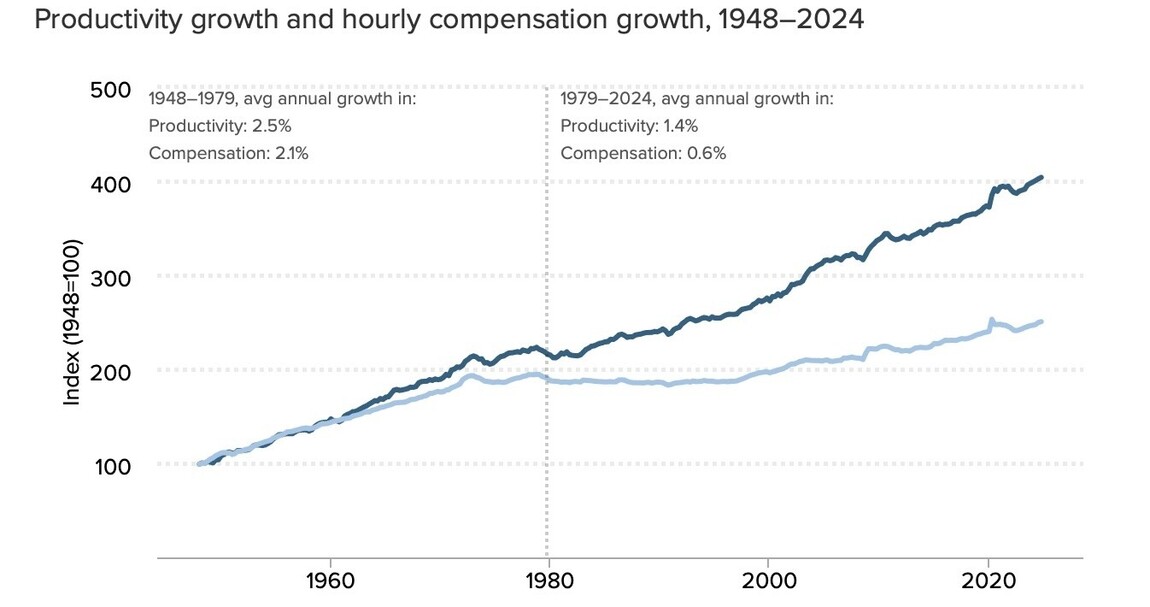

In the 1970s, the coupling of wages to GDP became a thing of the past in the States. In the post-war years, the GDP of the States increased along with wages. As GDP went up, so did the remuneration of workers. It stands to reason. A country creating such levels of wealth is best placed to ensure the spoils are shared and rightfully so. However, the de-regulation of the markets ushered in a new age of stagnant wages (36), even while the GDP of that nation continued on an upward climb. So what happened?

Andrew Yang – who ran for president in 2020 with a UBI platform (37) - writes about this in some detail in his excellent book on the subject to which I've already referred (27). In 'The War On Normal People', Yang writes that, 'Median wages used to go up in lockstep with productivity and GDP growth before diverging sharply in the 1970s. Since 1973, productivity has skyrocketed relative to the hourly compensation of the average age earner' (38). When presented graphically, the figures produce what's become known as the 'snake-jaws graph' (39):

It tells a story that isn't unique to the States. Indeed, it's recognised that, 'The “decoupling” of wages and labour productivity is a common phenomenon in many rich countries of the world' (40), albeit it happens at different rates and magnitudes (41). In the UK, it has been recognised that over the last forty years or so, there's been 'a 25 percentage point “overall decoupling” between productivity growth and median wage growth' (42). As to what the real world effects of this have been on wages, some have estimated the effects this last fifteen years to amount to a current shortfall of up to £11,000 a year on average(43).

Of course this isn't a perfect world and things aren't so cut and dry. There are also papers criticising such GDP/Wage models which argue that this phenomenon of 'de-coupling' is in effect almost zero when you take into account pensions, health benefits and the contributions of the self-employed sectors (44). Now I'm not going to pretend to possess any expertise here. To be honest, I was reading some of these economic papers with my head cocked the way a dog would if shown a card trick. That said, do you really need an academic background in Economics to know something's awry?

Whether it's Doctors, Nurses, Teachers, Railway and Steel workers, Healthcare assistants or Posties, suffice to say there's hardly a sector that doesn't seem to have taken to the picket lines of late. You can even have a look at strike calendars online to see who'll be downing tools and when (45), and from first glance it appears the diary's always full. Throw into the mix our modern problems of out-sourcing and the scandal that's the gig economy, and it's no surprise that UBI presents as a subject of much needed debate. As to how that debate proceeds and what informs it close to home, there are a number of pilot studies which have shed some light on it's real world efficacy.

Wales, Ireland and England Trials

In July 2022, a UBI trial started in Wales which targeted a particularly vulnerable demographic – those young people leaving the care sector. Over 500 young care leavers were provided a monthly income of £1,600 (before tax) to aid in what can be a troublesome transition from care to adult life (46). While the scheme has yet to be fully evaluated, initial findings have been positive, especially regarding young people's mental health, and has been cited as providing a means of informing 'future policy and practise for other parts of the social security system too' (47). That said, there has been criticism of the scheme from certain quarters.

Joel James, a Conservative Member of the Senedd, has raised concerns about funding, and has 'questioned claims that a universal basic income is being tested, suggesting care leavers were chosen to stifle opposition to the proposal'. He has also claimed that it is 'exactly the same as what is offered by existing welfare support', though that has been contended (48). Either way, the trial is to be stopped in 2025 and the final evaluation is not to be completed until 2027. That there's a Senedd election in May 2026, means the political landscape might change to the extent such findings are subsequently ignored. This would echo the state of affairs regarding the Dauphin trials in Canada if it came to it, but I sincerely hope that doesn't happen and that Cardiff University who've been charged with the analysis make their findings as public as possible.

In addition to the Welsh trial, a UBI pilot was launched in Ireland in September 2022 whereby 2000 artists and 'cultural workers' were awarded €325 a week for three years (49). Again, while a full evaluation has yet to be completed, the initial findings are very positive, with a whole range of beneficial outcomes being experienced by those involved in the scheme. As well as spending more time on their art, those receiving the basic income payments have reported suffering less depression and anxiety, were more likely to complete new works, and actually found it easier to find employment in their chosen field (50). So there's a lot to like here. That said, I do have my concerns.

My main problem with this trial – and this applies to the Welsh one as well – is that they have targeted a specific demographic. As such, they're not universal. And while basic income pilots go some way in highlighting the beneficial effects such schemes might have if rolled out, none of these studies go any way in emulating the Dauphin study, which successfully evaluated the effects at a wider community level. And although a pilot study is being rolled out by the think tank 'Autonomy' that better fits that 'universal' brief in East Finchley, England (51), only 30 participants will be taking part. Don't get me wrong, I'll certainly welcome their findings. But such a sample size won't provide the sort of big data we need here.

Scotland and Northern Ireland

As yet, no trials have been carried out in either. But that doesn't mean there's no interest. In Scotland, a feasibility study was carried out over two years by four local authorities (Edinburgh, Fife, Glasgow and North Ayrshire), with their 'preferred model for piloting a CBI pilot in Scotland […] based on 5 key principles: universal (paid to all); unconditional (no requirement to search for work); individual (not paid to households, like Universal Credit); periodic (paid at regular intervals); and made as a cash payment' (52). Bang on. Unfortunately, things seemed to have stalled since their final report into the matter in 2020, but I hope that's not the last we hear about it.

As for what's happening here, we have a local champion in the guise of Patrick Brown PhD*. Patrick completed his doctorate at QUB in 'researching the merit of Universal Basic Income (UBI) as a tool for conflict transformation in post-conflict societies' (53), and has extended his academic expertise by studying UBI and cash transfer schemes in South America. There he spent some time in 2023 during a fellowship with the Churchill Foundation, gathering data and performing interviews in both Brazil and Colombia. He's also been responsible for establishing the UBI Lab NI in 2020, and with the backing of 6 local authorities, is working towards a feasibility study for UBI in NI, which he argues can, 'increase social capital and build social cohesion, whilst also reducing many of the social ills which hold back deprived communities, including crime, poor mental health and, in the case of NI, paramilitary influence' (54). As such, this 'Peace Dividend' was at the heart of a proposal in 2020 that 'would aid conflict transformation in a post-conflict society such as Northern Ireland' (55), and it's been fascinating to read how these ideas have progressed from then to now under his auspice.

So if you would like to learn more about these developments at home and abroad, as well as gain further insight in to how a UBI scheme might be funded, please join Patrick and I on the accompanying Podcast to this article.

* Patrick is now Executive director of Equal Right, and their website is well worth a visit:

https://www.equalright.org/our-people

Links

1) https://basicincome.org/about-basic-income/

2) Guy Standing, 'Basic Income: And How We Can Make It Happen', Penguin Random House UK 2017 pp9-10

3) https://www.parliament.uk/magnacarta/#:~:text=Magna%20Carta%20was%20issued%20in,as%20a%20power%20in%20itself.

4) https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/magna-carta/charter-forest-1225-westminster/

5) https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2017/mar/04/basic-income-birthright-eliminating-poverty?ref=scottsantens.com

6) https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opendemocracyuk/why-youve-never-heard-of-charter-thats-as-important-as-magna-carta/

7) https://braveneweurope.com/guy-standing-let-us-celebrate-the-800th-anniversary-of-the-charter-of-the-forest

8) Guy Standing, 'Basic Income: And How We Can Make It Happen', Penguin Random House UK 2017 pp10-11

9) https://basicincome.org/history/

10) https://thecritic.co.uk/issues/july-august-2020/a-short-history-of-universal-basic-income/

11) https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1590&context=senior_theses

12) https://basicincometoday.com/thomas-paines-centuries-old-argument-for-ubi-as-a-right/

13) Guy Standing, 'Basic Income: And How We Can Make It Happen', Penguin Random House UK 2017 pp12-13

14) https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bertrand-Russell

15) https://basicincometoday.com/why-bertrand-russells-argument-for-idleness-is-more-relevant-than-ever/

16) https://basicincome.org/history/

17) https://socialpolicyblog.com/2018/10/25/an-idea-whose-time-has-come-the-return-of-universal-basic-income/

18) https://www.socialeurope.eu/44878

19) https://miltonfriedman.hoover.org/internal/media/dispatcher/214027/full

20) https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/negative-income-tax-explained

21) https://webapps.ilo.org/public/english/protection/ses/download/docs/wider.pdf

22) Rutger Bergman, 'Utopia For Realists: And How We Can Get There', Bloomsbury Great Britain 2017 p38

23) Andy Stern (with Lee Kravitz), 'Raising The Floor: How a universal basic income can renew our economy and rebuild the American dream', Public AffairsTM 2016 p166

24) Guy Standing, 'Basic Income: And How We Can Make It Happen', Penguin Random House UK 2017 pp162-163

25) https://thecorrespondent.com/4503/the-bizarre-tale-of-president-nixon-and-his-basic-income-bill/173117835-c34d6145

26) Andrew Yang, 'The War On Normal People: The truth about America's disappearing jobs and why universal basic income is our future', Hachette Books New York 2018 pp176-177

27) Rutger Bergman, 'Utopia For Realists: And How We Can Get There', Bloomsbury Great Britain 2017 pp34-37

28) Guy Standing, 'Basic Income: And How We Can Make It Happen', Penguin Random House UK 2017 pp16-17

29) https://basicincome.stanford.edu/experiments-map/

30) https://www.visionofhumanity.org/highest-number-of-countries-engaged-in-conflict-since-world-war-ii/

31) Max Tegmark, 'Life 3.0: Being human in the age of Artificial Intelligence', Allen Lane 2017

32) Martin Ford, 'The Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of Mass Unemployment', Oneworld Publications 2015

33) James Barrat, 'Our Final Invention: Artificial Intelligence and the end of the Human Era', Thomas Dunne Books 2015

34) https://builtin.com/articles/industry-risk-replaced-ai

35) https://hbr.org/2023/04/how-generative-ai-could-disrupt-creative-work

36) https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2018/08/07/for-most-us-workers-real-wages-have-barely-budged-for-decades/

37) https://2020.yang2020.com

38) Andrew Yang, 'The War On Normal People: The truth about America's disappearing jobs and why universal basic income is our future', Hachette Books New York 2018 pp14-15

39) https://www.epi.org/productivity-pay-gap/

40) https://www.productivity.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/TeichgraberIPM_41.pdf

41) https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w19136/w19136.pdf

42) https://www.lse.ac.uk/News/Latest-news-from-LSE/2021/k-November-21/Wages-of-typical-UK-employee-have-become-decoupled-from-productivity

43) https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/mar/20/uuk-workers-wage-stagnation-resolution-foundation-thinktank

44) https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/cp401.pdf

45) https://www.strikecalendar.co.uk

46) https://www.gov.wales/wales-pilots-basic-income-scheme

47) https://www.salford.ac.uk/news/universal-basic-income-wales-is-set-to-end-its-experiment-why-we-think-thats-a-mistake#:~:text=The%20trial%20involved%20paying%20monthly,initial%20feedback%20has%20been%20positive.

48) https://www.southwalesargus.co.uk/news/23881345.welsh-government-end-basic-income-pilot-scheme/

49) https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/employment/unemployment-and-redundancy/employment-support-schemes/basic-income-arts/#:~:text=pilot%20scheme%20work?-,What%20is%20the%20Basic%20Income%20for%20the%20Arts%20(BIA)?,most%20up%20to%20date%20information.

50) https://www.socialjustice.ie/article/basic-income-artists

51) https://autonomy.work/portfolio/basic-income-big-local/

52) https://www.basicincome.scot/news/articles/exploring-the-feasibility-of-a-citizens-basic-income-pilot-in-scotland

53) https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a7b08c0d0e628f80b2cce36/t/5f7b2810927caa7f7aedd00b/1601906746178/A+proposal+for+Universal+Basic+Income+-

54) https://media.churchillfellowship.org/documents/Patrick_Brown_Final_Report.pdf

55) +UBI+Lab+Northern+Ireland+-+Oct+20.pdf